A Young PIO in the Dark Ages: My Early Days at East Bay MUD

David Vossbrink, APR, Communications Counsel

When I began my public information career nearly a half century ago, there were no fax machines. Today, no one uses fax machines anymore. We mailed our news releases through the U.S. Postal Service. Our most modern technology was portable electric typewriters. There was a news cycle for the morning and evening papers, and television news used film.

Although we didn’t have the same box of tools that communicators use today, we did have earlier incarnations. And the fundamentals of good public communications were the same then as today. Truth and accuracy and respect are essential for PIOs. We must engage with our critics and adversaries on matters of policy with mutual listening and learning, and hopefully leading to consensus. Good service means we return calls and do the research to help news media and the public. Good writing and effective storytelling are critically important skills.

In the early 1970s I was a rookie public information representative at East Bay Municipal Utility District, the big urban water supplier to a million people in Alameda and Contra Costa counties. I had discovered our profession by accident (don’t we all?) when I was a community organizer as a VISTA volunteer on the wrong side of the tracks near Fort Lauderdale.

As an organizer fresh out of college, I learned that people could have power to create change if they came together. I learned that I could connect reporters with stories that weren’t getting told, stories about the people in the poverty communities who were trying to get decent schools, safe drinking water, and better job opportunities.

I learned that local government had the greatest impact on quality of life in these communities, and that it was also the most accessible and receptive to possible change compared to the distant state and federal governments (some things don’t change).

And I learned I had skills that I took for granted: I could write and break down problems; I wasn’t intimidated by people in neckties and I could get along with people who didn’t look like me; I was patient. It was on-the-job training with no teachers for a career I didn’t yet know existed, and it prepared me enough to land an entry-level job at EBMUD when I returned home to Oakland after a year in the field.

I was doing PR for poor people, which I didn’t realize until my job interview.

As VISTAs working with our neighbors, we helped them raise hell about the housing authority, made local elected officials nervous when a busload of upset residents came to county commission meeting, and scared the rest of town about a serious potential health risk by talking to the news.

Reflecting back now, the District took a risk when my boss hired me, a smart-ass rabble rouser who talked a good game. Ah, the arrogance and innocence of youth. I didn’t really know that much about communications, public relations, local government—or water management, after all, so EBMUD was where I finally got my real professional training from the savvy pros I was fortunate to work with for the next ten years.

News releases and “new” technology

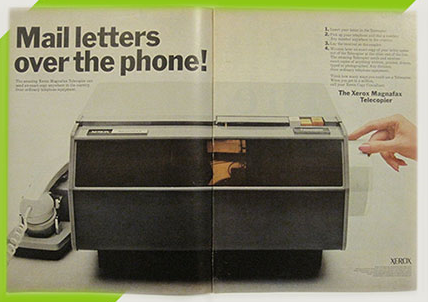

Technology was definitely old school. Our public information office had just acquired a new “telecopier” around the time I arrived, so we now could send documents to EBMUD’s Sacramento office immediately. This was hot stuff, cutting edge office technology in the early 1970s. But that message had better be important to warrant the time and the long-distance phone charge: six minutes a page, and it required compatible machines on both ends and rolls of special paper to receive a transmission.

The early version of the fax machine

was too new and too slow to distribute batches of news releases.

Instead, we mimeographed (!) releases so that we could collate,

staple, fold, and stuff them into envelopes to take to the

mailroom. USPS was our state of the art distribution system, and

it worked. Releases usually were delivered the next day if we

were able to make the 4:00 p.m. cutoff at the mailroom for the

last post office run of the day.

The early version of the fax machine

was too new and too slow to distribute batches of news releases.

Instead, we mimeographed (!) releases so that we could collate,

staple, fold, and stuff them into envelopes to take to the

mailroom. USPS was our state of the art distribution system, and

it worked. Releases usually were delivered the next day if we

were able to make the 4:00 p.m. cutoff at the mailroom for the

last post office run of the day.

Beat reporters for the dailies—the Oakland Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, and SF Examiner—got the story first, of course, but the community papers and the weeklies were happy to get our releases a day or even two days later. We would write up what we considered the lead story ahead of the biweekly EBMUD board meeting, and then keep our fingers crossed that the board decision matched the lede we wrote. Otherwise we would have to redo the release and miss our mailing deadline. In those days, however, we didn’t get too many surprises.

Our team had built a strong trust relationship with local reporters who couldn’t cover meetings and relied on us to call them about the news and board decisions. Some reporters I never saw face to face for years, but we had regular conversations about operations, policies, and politics for the District. They trusted us for the facts, and their stories were timely and accurate.

Cut and paste

We wrote those news releases, and all our copy, on brand new

Smith-Corona portable electric typewriters, a significant

technology improvement, that replaced the Royal Standards that

had graced the Public Information Office just before I came to

East Bay MUD. The cut-and-paste function was exactly that: we

would type our drafts on cheap yellow paper, and then take

scissors and rubber cement to rearrange sentences and grafs. What

a mess.

We gave the reassembled strips and markups to secretaries in the office (though not to the typing pool upstairs—that served the engineers, and PIOs were “special”) who cleaned up our copy for another round of review and editing. Finally a draft was ready for “clearance.” That meant routing the draft to a half-dozen (or more) technical and management reviewers for fact-checking and approval via interoffice mail in those big manila reusable envelopes with red string.

If time was short (as it usually was), we’d walk the draft around the offices and hover over engineers at their desks to get their initials of approval (and their picky technical edits that we often ignored, or negotiated about). Ideally there were minimal changes.

Clearance could take days, even weeks, depending on the topic, the length of the document, and its sensitivity and complexity. We didn’t have email or Google Docs or track-changes to allow multiple reviewers at once; it was a serial process, and everyone in the approval chain wanted to see who made what changes.

Then the draft finally came back with the general manager’s imprimatur (nothing got mailed without that), triggering the distribution of a release, or starting the design and production of a brochure or a report.

Later in the 1970s we acquired an IBM Magcard “smart typewriter” that made changing drafts a lot easier. But the secretary operating the Magcard could see only a line of type at a time on her “screen” (secretaries were always women in those days; we didn’t get our first woman PIO until around 1980), and she had to remember exactly where she was on an invisible document without losing her place to key in the edits. It’s was a tricky skill to master, and not everyone could do it.

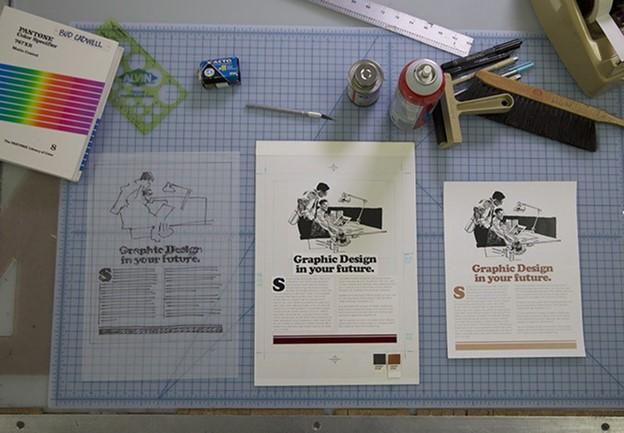

Hot type and mechanicals

Once we had final copy, we could get on with graphic design for

bill inserts, annual reports, and District brochures of all

scales. In the days before Adobe Photoshop or InDesign or

Microsoft Publisher, we worked with contract designers who would

send our copy out to a typesetting shop. This was during the long

transition from “hot type” where text was printed from molten

metal, to the new “cold type,” or phototypesetting that required

big computers.

Either way, we got back long strips of galleys for proofing and correction that the graphic designers would then cut up and lay out on boards for “mechanical separations,” or paste-ups. If we were printing in several colors, each color required a separate acetate overlay on a cardboard base to indicate were the photos and graphics were to be “stripped in” using “Rubylith.” There’s another old-school technical skill that’s been replaced by computers.

And we commissioned a lot of photography—on film, of course, using Nikon and Rolleiflex cameras. Binders upon binders of color slides were stored on the shelves in our office, and bundles and bundles of black and white negatives and proof sheets were kept in the drawers. Our indexing was hit and miss, so we had to rely on our collective memories to locate the right images to use for our publications.

Telephones

Perhaps the most critical of our available technologies was the

telephone. We had the old rotaries, with push buttons for

different extensions and a red button to put a call on hold. I

still miss that winking hold button after all these years—it was

intuitive and we didn’t need a manual to learn to use

it.

No cell phones, of course, and no Zoom, but phone booths were everywhere. But not necessarily where you needed one most.

This became painfully clear during a serious emergency in 1981 when East Bay MUD’s Mokelumne Aqueducts, which delivered water to a million people, were threatened by flooding from the failure of an adjacent Delta levee.

We dispatched a member of our PIO team to the Delta every day to join the scrum of farmers, water agencies, state officials, railroad operators, construction contractors, and District reps who stood in a big circle every morning in a farmer’s barn in the middle of nowhere to share information, learn the status of the flood and repairs, and discuss next steps.

But to get that urgent information back to headquarters in Oakland so the rest of team could update the staff, media, and the public, we had to rush to the nearest payphone after the scrum. It was located a couple of miles away at a tavern on Highway 4 west of Lodi. Just one pay phone, and dozens of people needing to use it immediately. So a pocketful of dimes also was necessary equipment, and good running shoes to get a head start to reach that phone first.

Media tours

Every spring when the hills were green, our PIO team organized community tours to visit EBMUD’s dams and aqueducts in the Sierra foothills. It was an overnight trip (usually Friday and Saturday, but no overtime pay for us), and they included our running commentary about water issues, history, technical matters, along with lots of food (my first boss was fond of the two-hour lunch, lubricated, of course).

For several weekends in April we would fill a bus with people from service clubs such as Rotary and Lions, a scattering of elected officials, and neighborhood and business leaders from all over the East Bay. Our high tech data base for inviting participants was a shoebox of index cards, shuffled and reshuffled, added and discarded, as the tours progressed over the years.

Then there was the annual media tour to the water works. Same itinerary, but no agenda except an open bar and poker games when we got there. We called it “relationship building,” of course, and it was a popular event for our local reporters. We just had to make sure everyone got back on board in one piece, and that no loud noises would disturb their sleep on the road home.

That media expedition ended with the post-Watergate era when news media discovered ethics and conflicts of interest. When reporters had to pay for the trip and justify the expense to their editors, they no longer signed up. Perhaps for the best—it would pass the sniff test in these more proper days, but the press corps did miss the trip.

The Fundamentals

So our communications technology certainly has changed over the past fifty years, but the principles of good communication that I was fortunate to learn and practice in my first PIO job haven’t:

- Telling the truth is where we must start and where we must remain.

- Know your audience and respect it, and go to where they are (and feed them) rather than make them come to you.

- Engage your critics, don’t dismiss them—you might have technical expertise, but they are experts about their lives and their perspectives.

- Public relations is a two-way street that requires listening as much as talking. It’s about relationships, not transactions.

- Bad process trumps good policy, because good policy requires public trust based on inclusion and good information.

- Good writing has always been essential, along with good storytelling.

- Return your calls.

- And the mic is always on.

dvossbrink@yahoo.com; 408-368-5637